Electron energy levels

The Bohr model gives almost exact results only for a system where two charged points orbit each other at speeds much less than that of light. This not only includes one-electron systems such as the hydrogen atom, singly ionized helium, doubly ionized lithium, but it includes positronium and Rydberg states of any atom where one electron is far away from everything else. It can be used for K-line X-ray transition calculations if other assumptions are added (see Moseley's law below). In high energy physics, it can be used to calculate the masses of heavy quark mesons.To calculate the orbits requires two assumptions:

- Classical mechanics

- The electron is held in a circular orbit by electrostatic attraction. The centripetal force is equal to the Coulomb force.

- where me is the mass, e is the charge of the electron and ke is Coulomb's constant. This determines the speed at any radius:

- It also determines the total energy at any radius:

- The total energy is negative and inversely proportional to r. This means that it takes energy to pull the orbiting electron away from the proton. For infinite values of r, the energy is zero, corresponding to a motionless electron infinitely far from the proton. The total energy is half the potential energy, which is true for non circular orbits too by the virial theorem.

- For positronium, me is replaced by its reduced mass (μ = me/2).

- Quantum rule

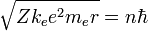

- The angular momentum L = mevr is an integer multiple of ħ:

- Substituting the expression for the velocity gives an equation for r in terms of n:

- so that the allowed orbit radius at any n is:

- The smallest possible value of r in the hydrogen atom is called the Bohr radius and is equal to:

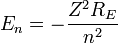

- The energy of the n-th level for any atom is determined by the radius and quantum number:

The combination of natural constants in the energy formula is called the Rydberg energy (RE):

is the rest mass energy of the electron (511 keV)

is the rest mass energy of the electron (511 keV) is the fine structure constant

is the fine structure constant

When Z = 1/α (Z ≈ 137), the motion becomes highly relativistic, and Z2 cancels the α2 in R; the orbit energy begins to be comparable to rest energy. Sufficiently large nuclei, if they were stable, would reduce their charge by creating a bound electron from the vacuum, ejecting the positron to infinity. This is the theoretical phenomenon of electromagnetic charge screening which predicts a maximum nuclear charge. Emission of such positrons has been observed in the collisions of heavy ions to create temporary super-heavy nuclei.[citation needed]

The Bohr formula properly uses the reduced mass of electron and proton in all situations, instead of the mass of the electron:

. However, these numbers are very nearly the same, due to the much larger mass of the proton, about 1836.1 times the mass of the electron, so that the reduced mass in the system is the mass of the electron multiplied by the constant 1836.1/(1+1836.1) = 0.99946. This fact was historically important in convincing Rutherford of the importance of Bohr's model, for it explained the fact that the frequencies of lines in the spectra for singly ionized helium do not differ from those of hydrogen by a factor of exactly 4, but rather by 4 times the ratio of the reduced mass for the hydrogen vs. the helium systems, which was much closer to the experimental ratio than exactly 4.0.

. However, these numbers are very nearly the same, due to the much larger mass of the proton, about 1836.1 times the mass of the electron, so that the reduced mass in the system is the mass of the electron multiplied by the constant 1836.1/(1+1836.1) = 0.99946. This fact was historically important in convincing Rutherford of the importance of Bohr's model, for it explained the fact that the frequencies of lines in the spectra for singly ionized helium do not differ from those of hydrogen by a factor of exactly 4, but rather by 4 times the ratio of the reduced mass for the hydrogen vs. the helium systems, which was much closer to the experimental ratio than exactly 4.0.For positronium, the formula uses the reduced mass also, but in this case, it is exactly the electron mass divided by 2. For any value of the radius, the electron and the positron are each moving at half the speed around their common center of mass, and each has only one fourth the kinetic energy. The total kinetic energy is half what it would be for a single electron moving around a heavy nucleus.

(positronium)

(positronium)

No comments:

Post a Comment